(This interview was originally published in Greek in the deuxelles.gr website)

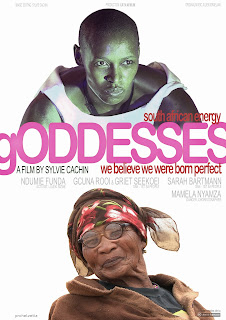

Deux Elles has something really special for you today, March 8, to celebrate International Women's Day. It's an interview with Swiss film-maker Sylvie Cachin, whose film "gODDESSES" was screened at the 14th Thessaloniki International LGBTQ film festival. This wonderful documentary negotiates the subject of the shift in the habits of African societies, after colonialism, in terms of the perception of gender issues. Women who speak in front of the lens, explain the harmony that existed before colonialism in the societies of indigenous Africans, and through their experiences of domestic abuse and rape of African women today, we realize the gap and the contrast between then and now - on one side, stands gender equality, a story of the past, and on the other, men's need today to control women and to punish them, even with rape, because of their sexuality, which is something they do not understand, as stated in the film by a 28 year old lesbian, Aneliza Mfo, who was raped at gunpoint in 2008. "You thought you were a man but you got a lesson" the rapist said to her as he was leaving. Such kind of "corrective" rape, although outrageous in concept and realization, is unfortunately a common occurrence in today's African communities. Sylvie Cachin was kind enough to give Artemisfree an exclusive interview which discussed at length a number of interesting issues that are relevant to LGBTQ community worldwide today.

A. Why did you name the film "gODDESSES" and why is the first letter in lower case?

S. Sure, I do not believe in transcendental gods or goddesses : goddesses are on earth, in each of us; we are goddesses. Meaning, we, women, are strong, independent and able to create our own structures of life ... : this assertion is partly a concrete reality, partly a programmatic statement, an impulse to a wider emancipation of women; that I share with the women I met for the film.

A. How much are you involved into women rights issues in your own life? One of your interviewees, in the film "gODDESSS", Ndumie Funda, starts an activist organization because one of her friends was murdered. What are your own experiences on these matters?

S. I am not an activist, but a creator. I could say that I became aware about the issues regarding men and women power when I was around 13- men work, women stay at home. I grew up in Switzerland, in the country side, my parents were left-wing, not activist at all, a bit into politics, but not much. I studied literature, history of art, and history in general, and I noticed how women's point of view and women's history was not included.

A. We are taught history here in Greece and it's all an account of constant battles and war and conflict as well.

S. Yes, about politics and land and power. Women are not included. Artists are not included. Maybe you will hear about Picasso or Dali, but not Frida Khalo. This baffled me a lot. But I did not become an activist. There was no such culture or movement around where I grew up. To make a long story short, when I started to make films, I dived into myself. I expressed my own thing. It was about me, growing up in the country side. My identity was not named. I had problems with my mother's homophobia. I grew up through my first film. My first film is a depiction of the life of a lesbian. Ten years ago I met activists. I learnt that being an activist can be a main occupation, like a profession. I was surprised to see that.

A. If they were doing this only part-time, it wouldn't be effective, right?

S. Exactly! I was glad that I was able to attend a workshop, organized by a few Swiss Germans, people from Eastern and Western Europe, artists and activists together. It was a 3 day workshop in the Swiss mountains, in Salecina. We met, we talked, we discovered each other's universe. That was a turning point. Later, when in Geneva, I also met activists, and then I begun to be conscious and be aware of myself as an activist film-maker in a way. But first of all I am a film director. My films have a political message. So, in this way, I am an activist.

A. You can be an activist in many ways. And creating something that has a message can actually be very effective, because it is quite loud! It can be perceived and understood by many people. Can you tell us more about the message of your film?

S. It speaks about connecting with the roots that existed before colonialism- before the Europeans came to South Africa and brought with them their system of hierarchy, their politics and their violence. In the film we see the indigenous people and their values. We could learn from these values. The gender equality- no politics.I don't know if we could go back there, but just to remember it - we could be and should be influenced by these values. The women were much more considered. The women were in the center of the society. They gave birth. They were connected to the earth. They were strong. This is also connected to gender equality. Matriarchy is not the mirror of patriarchy. Matriarchy is a different kind of organization of a society. Where you respect the women for giving birth, you respect birth, children, the human being, and earth itself. The historian interviewed in my film expalins: “if you were born as a boy or a girl, it did not matter. What it mattered was that you were born.”

A. In our country I think fathers are slightly more proud if they have a boy rather than a girl (laughs). Can you tell us more about this kind of indigenous society and how it worked?

S. They had a kind of gift economy. They did not have money. Some of them could hunt, others would gather... and they would exchange. There was no possession of land. They did not have this value of possession. They did not have to fight to be where they were. They considered themselves equal to plants and animals. They respected plants and animals alike. They spoke to plants and animals. In the film you see a woman eating a kind of cactus. It was great as a means to preserve themselves when they were walking through the desert and they had nothing to eat or drink. It would give to the body what it needed. So, this woman, she would treat the cactus carefully before eating it. It was not something done for the camera. This is how she was.

A. The way we lead our lives today, especially in the cities, people are completely separated from nature. We think that we can control nature. We live under the illusion that we can do whatever we want with it.

S. It's a tragedy what we are doing with nature. We must evolve our consciousness towards nature. South-africans today, they are disconnected from nature. They only now re-discover ecology. Our respect for nature, for animals, is linked to respect for people. Destroying nature we are destroying ourselves. This makes me feel very angry. What happened in Japan, for example. I cried a lot, because the sea was damaged. I was sorry for people too, but I think it happened because people there are following this idea of always doing more, and more, and more. And it seemed like the Japanese were looking for it. They are so arrogant when it comes to the treatment of nature. They do not respect nature. When I was in South Africa, I had this feeling... Nature there is huge, the horizon is so wide, and you are like a small bug in the middle of this huge land.The energy there was strong and I could feel something - like wow - I could understand respect towards nature. There were lions and baboons and elephants and the humans were only a small part of it. So being a human is not such a huge thing as we think it is.

A. Let's go into a different topic. The structure of family in the western world as opposed to the one described by the KhoiSan culture. In the west, obviously women today are in a better situation than before, but still, not as good as they should be. What is your own experience?

S. My mother was very independent. When she married my father, she decided to stop working to enjoy her family life because she loved her children. She did this for 15 years. When she was in her 50s she went back to work. It wasn't very easy but she found work. At 75 she got fed up with my father and she walked away. She divorced him. For the 15 years, when she was a housewife, she obviously did not have any kind of job insurance, of course, which means that when she needed to receive her pension, later, she couldn't. My father gave her pension, of course, but she did not have her own pension. So, she had this disadvantage, by the society, because she was a mother and she raised her children. This is a problem of law, in the society, that does not give the same things to men as to women. This is that I could observe. And I continued to observe, as a film-maker, that there are not many female film directors, for example. Today there are more, and I am really happy to see this. But when I was in the university I saw that there were a lot of teachers who were men and they were very misogynist. Men, when they notice women who are strong and talented, they seduce them, to get information from them. They are fucking them and taking their knowledge to grow up, but not to be proud of these women. They become parasites to grow up because they are ambitious. I had many friends in the university that experienced this. I had a friend, in particular, in the university who went through this - they tried to steal her ideas.

A. Did you personally feel limited in some ways, by your co-workers who are men?

S. Not really, but I remember once, when I made my diploma film, the guy who was responsible for giving the money, acted like a real "macho" guy. You had to seduce him to get the money for your film. Most of my friends did it to get their films done. This guy is a bit of a caricature and in my opinion was he was not even a good film-maker. He had very commercial ideas. Anyway, he was in this position. He was a weak guy who was taking advantage of a position of power. When I met him, I could not stand this. I said I can do my film without your money. I did not have a fight, I was just myself. I told all my friends about this. Nobody reacted. Two years later they had to go through this and they came and told me about this guy, that he is a bastard, etc. And I told them, haven't I said this to you two years ago? I am noticing such people, men, who use their power - of course it could also have been a woman. But for men it's easier to act like this, because we have a long history of male domination. So, I was limited, in a way, in this case, by the fact that I did not get much money to do my film. But I found other ways to do the film anyway.

A. What about the daily life?

S. In the daily life I am always bothered by male attitude. It is getting better, but still. When you go to a bar, obviously, if you are alone, the guy is meant to come and offer you a drink. You say no but they insist. I am getting angry when this happens. Still they feel they have the right to do this.

A. Do you say no, I am a lesbian, I am not interested? And then they get even more interested because you said that? (laughs)

S. It's not a good argument to say I am a lesbian. It's not the way to get rid of them. I don't say it. Because it's not the reason. I don't like him. I say "I don't like you". (she points and laughs)

A. Do they get it?

S. No!

A. They still dont get it?

S. No!

A. Ok. Change of subject now. I hear in Greece from homosexuals that are (usually) closeted that it's not right to go out in the Pride Parade with feathers up your ass and dance, because this is an extreme image and it does damage to the community. One of the things that I wanted to ask you, was, have you encountered in your life this kind of attitude? Some sort of internalized homophobia.

S. It's complex. There is a private life, a social life, and also, a public life, lately, for me. It evolved, for me personally. I think I am late. For example, when I was a teenager, I was ...nothing...now I am much more conscious of my identity, I am speaking out. I can tell you some clues about my life. One of my first short films I made was inspired by my own story, the story of two lesbians. It's called "L' Amalgame" (1998 ). I made my own story into fiction and it was all about internalized homophobia. When people were asking me what the film was about, I would say "oh it's about the relationship between two persons". I was like "why should I talk about myself in this way", you know? When you meet a person, no one shakes your hand and introduces themselves "hey I am hetero", so why should I say "hi I am gay". I think the reason why I did not say these things was that I was scared to talk about myself because of the reaction of my mother when I came out to her. She knew I had a relationship with a woman so she asked me, "are you a lesbian? Cause if you are, you are making me sick, you are a whore, blah-blah", so in a way she told me, "if you are with a woman you don't have my love anymore".

A. It was a kind of an emotional blackmail...

S. Yes. I think I was conditioned by this. I saw disgust in my mother. Her disgust came not from me, but from a certain image she had about this, of me as a lesbian. So I had a fundamental anger, not so much against my mother, but against the society around my mother which made her think like this. To analyze all this emotional pressure, and to overcome this, it's long work, it's fucking long work! I think I work with his in my films too. Now I am ok, but it took a while.

A. I think every person in the LGBTQ community has to go through this one way or another.

S. It's not easy to deal with this, because in an unconscious level, we all want to be proud of ourselves, of who we are. In a way, artists have the time to explore their complexity, to think about who they are, why they are. I think my role is, with what I am doing, I am "reading" myself, as I grow up, and I am trying to give meaning, to show pictures of others, but through me. I am using me. I am my own subject. Even in documentaries. When I was in South Africa, for example. I went to an artist's show. After the show, I met her, we talked, and we introduced ourselves. And after two minutes, she said to me "I am a lesbian". I was introduced to several lesbians who could easily tell me: “I am a lesbian”. They have a strong consciousness and pride of their identity as lesbians. It's a different culture. I was not able to say it like this: I am a lesbian. I never did that before. It's a different culture. They are so much stronger. Much stronger than we are. They are much more proud. They have real pride.

A. So you said this yourself, too "I am a lesbian" for the first time.

S. Yes. No, my “coming out”― came much earlier. But I became more free in not censoring myself in a public sphere.

A. Isn't accepting yourself the first step, so that others can accept you as well? How can you expect from others to accept you if you don't do it first?

S. Yes it's necessary. I am not sure I am at the end of my way of being totally free of being myself. But I am much more free now. And I think that South Africa gave me a good inspiration.

A. You stayed there for six months! You put a lot of work into this. The story just flows. I was very interested in watching what was going on, all the time. I loved it. How come you went there in the first place, and how come you spent so much time there?

S. It's an interesting story and a long story. In Geneva there was an ILGA conference, and there were a lot of African guys, and I stayed there for one week. I met Africans for the first time, activists and South African women. And we had this connection. I met a woman activist ... During this time I was interested in matriarchy, and I asked her about this concept. And she told me this thing: "not only I believe in matriachy, I know it will come back". So, I said "wow - how can she have such strong beliefs". So, I thought I was holding a very good thing for a film. Somebody who believed so strongly in this. This was my starting point. But only five years later I had the opportunity to get a residency in South Africa. It was a residency by the Swiss government for artists to stay in South Africa. I could stay there for 3 months or 6 months and do a small project, a film. I wrote a pitch about matriarchy, about these indigenous people living with gender equality, and nowadays living in South Africa with gender based violence. And this idea came from this activist. I asked her, what could I do in South Africa, and she thought of this concept and we could work around this. I was surprised I got this residency.

A. How come you stayed there for so long? Was it because of the program or did you need all that time to complete the film?

S. It was my decision. How I spent my time? I needed the time to feel it, to understand better their point of view, to see how they reacted in different situations. To live with them. I didn't want to just be the external eye and be there, get a quick interview and do a quick editing etc. So we got the problematic down in one hour. But I needed to share. So that's what I did. I spent 3 months for the shooting, not every day of course, and recorded 13 hours on tapes, I think it’s not much.

And one month and a half before I left, I did not use my camera any more. I didn't touch my camera because I didn't want anybody to blame me for being superficial, for a European point of view and do just another movie about South Africa and violence- no way. I mean, I left my usual position as a camerawoman and tried to feel with my body this society. Because they are so physical, there is such rhythm, they sing, they dance, they hug, all these together.

A. The film also felt organic to me. You managed to speak in a way, as if you lived it, you did not try to approach it intellectually.

S. But I did it also intellectually, on both levels. Like in my film, there is someone who is a dancer, someone else who is an intellectual, there are bushmen etc. All these levels.

A. Where you live, in Switzerland, how is society treating black people?

S. Good. It is not an issue. Geneva is a cosmopolitan, very mixed environment. I can walk for five minutes in my neighborhood and not hear French because there are so many people from different cultures. Black are not different than other cultures in Geneva. They are not rich, but they are comfortable. Not all of them, but some of them, they open bars, they have their own jobs etc.

A. In Greece, it's different. Black people are kind of invisible. No one pays attention to them or knows their culture. They live by illegal trade and police usually chase them for that.

S. I had no connection with black people before I went to South Africa. I used to hear all different kinds of prejudices

A. What about homophobia?

S. There used to be this idealistic image about Switzerland, that it is a kind of cocoon, that to live there it means to live in extreme comfort. Now everything has changed, especially in the past ten years. Anyway, homophobia is not a problem anymore, gay people are more visible, in the media as well. Back in 1995, when I started making films, I thought someone must talk about lesbians, in film, because they do not exist! I hope I had something to do with this! When I finished school there were more lesbian directors out there. People's minds changed with visibility. I think there is still work to be done in schools. To teach kids about homophobia. There are some people who, by the way they see you, by their opinion, they put you in a kind of jail. You understand me? It's in their eyes. They put you to shame.

A. They imprison you in an invisible jail. How can someone think that love is a thing to be ashamed of?

S. And all of us internalize this opinion. Even when we are conscious. It happens to me. I cannot

control it. I am not free from their opinion. I am totally angry with this. I think that this is the impact of religious values.

A. I dont think this is a party of true spirituality. It's a view basically poisoned with biased moral views. I see this especially in the older generation, and especially in women who go to church. They are not comfortable with their sexuality. I don't think they ever had pleasure in their life.

S. Οf course, look at them. They are so frustrated.

A. In the past few years I see more and more gay people being happy.

S. It's evolving.

A. Especially the new generation. They are happy and comfortable with themselves. There is something important we haven't covered and that is the way the film was received in different countries.

S. Perhaps the most interesting one was in Ethiopia in a Human rights festival, which they could not name specifically as Human Rights festival because of the government who forbid to talk about this. So they call it International Film Festival. Some people from the Kenyan government attended the screening. They asked me if I was promoting lesbians. (Homosexuality is still considered as a crime in the ethiopian law). My answer was, and I was very glad I could give that answer, "I am talking about South Africa where, after the white oppression – the Apartheid time – the government gave equal rights to all kind of communities, as well to the gay community. Black Lesbian Women are three times oppressed. Because they are black, because they are women, and because they are lesbian. They are murdered because of their identity". They did not say a word back. Then, there was the experience in South Africa, a mixed students audience, around twenty years old, and so many of them they were laughing at some daily scenes, seeing their own people on screen. They were embarassed by the theme of homosexuality : they said «We are speaking too much about gay people in dance industry». In Johannesburg, I showed the film to young lesbians from the country who loved the film, they thought it was very educational and said that it’s good to see that hiding or blaming ourselves is not the solution. In Switzerland they asked a lot about how I met these lesbians, about the freedom of being gay in South Africa. Ιn Thessaloniki, the audience asked me how did I make the film. If it was difficult to make. It was the first time I could speak about the conflict I had because I am European, because I am a potential neo-colonialist. I could speak about this. Sometimes it was difficult to deal with people in South Africa, because they accused me of making benefit out of the film, out of using them. It made me angry because I am poor like them. I paid for this film and I am still paying. I am glad I could talk about this! I gave a lot of energy to do this film.

A. Is there something you would like to talk about,that we haven't covered in this interview so far?

S. I would like to talk about my evolution, while I was there. I spent 6 months there in South Africa, and then another six months, back in Geneva, in editing. I see black women taking back the power, slowly: empowered women. I enlightened their growing power in my documentary, and reciprocally I was given so much energy. It's not a documentary only made for an audience, it is part of my life, it was my own experience.

A. Thank you for this interview!